The High Cost of a Jobless Farm: Why Replacing One Industrial System With Another Isn’t the Green Solution We Think It Is

Share

The global conversation around food, climate, and technology is increasingly shaped by a single idea: efficiency will save us.

In the race to feed the world while "saving the planet," the spotlight has turned to industrial hydroponic farms and vertical grow systems. These operations are housed in sleek shipping containers or sprawling warehouses, often lit by blue-pink LED lights and run by automated systems. They promise high yields, low water use, minimal space requirements, and predictable outputs. On paper, they seem like the future.

But what if they aren't the future we actually need?

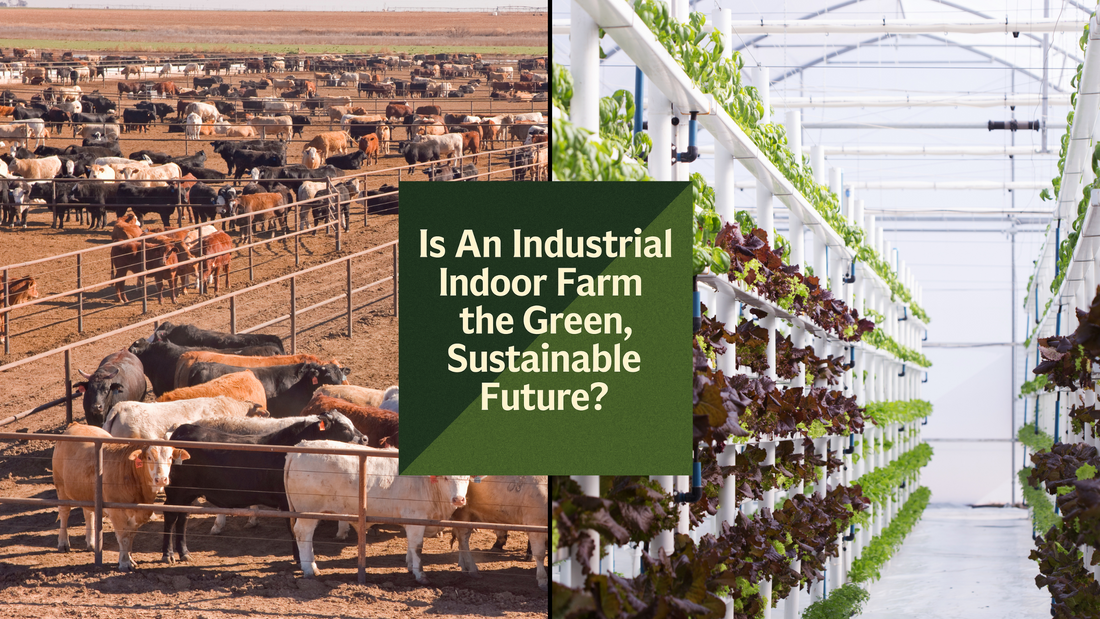

Replacing the Feedlot With a Lettuce Lot

At first glance, moving from a feedlot full of confined cattle to a climate-controlled hydroponic farm growing microgreens sounds like progress. But peel back the layers, and the parallels are startling.

Both systems:

- Rely on intensive inputs (electricity, automation, imported materials).

- Are disconnected from the soil and its life-giving cycles.

- Remove the human element from food production.

- Treat food as a product, not part of a living, breathing ecosystem.

Hydroponic systems are often framed as a solution to the very problems caused by industrial agriculture. But in truth, they are often just a different flavour of the same problem.

But Wait—We Grow Microgreens Too

This might sound surprising, especially since we ourselves grow microgreens indoors, under lights, in a climate-controlled environment. Why? Because it allows us to extend our growing season through the winter. It provides our community with nutrient-dense greens year-round. But here’s the key difference:

We aren’t trying to feed the world. We’re trying to feed our community. And we do it differently.

Unlike most industrial indoor farms, our growing system is designed to stay human-scaled and community-rooted. Yes, we grow microgreens indoors with controlled lighting and temperature, especially through the winter. But that’s where the similarity ends. We do everything else by hand:

- We sow seeds manually.

- We harvest with care, not with machines.

- We package and label our greens ourselves.

- We deliver them locally, door to door.

There are no £10,000 seeding machines here. No robotic harvesters. No automated conveyor belts. Our system is about relationship, not remote management.

We aren’t interested in producing for national distribution or maximising profits by eliminating people. We’re interested in building a food system that can be sustained by real people for real communities.

Because food, at its core, should be a local act. An act of nourishment, trust, and shared responsibility.

The "feed the world" narrative has been pushed on us since childhood. Remember being told to eat because of the starving children in faraway places? That narrative has shaped generations—but it’s worth questioning.

Why are we obsessed with feeding the world when we haven’t figured out how to feed our own country?

Here in the UK, we have children going hungry, people homeless and jobless, families falling through cracks. Yet so much effort is poured into creating solutions for somewhere else. Shouldn’t the first priority be building a food system that feeds and supports our own population—sustainably, locally, and fairly?

Only when we’ve done that can we meaningfully offer help beyond our borders.

The Carbon Cost of "Green"

A hydroponic farm may not run tractors or spray pesticides, but it trades those for constant electricity demands. Climate control, grow lights, water pumps, and automated seeders all require energy—and unless powered by a genuinely clean grid (which most are not), that energy still burns fossil fuels.

Even when systems are solar-powered, we must ask: what was the cost of producing that solar infrastructure? Mining rare earth metals. High-emissions manufacturing. Global shipping routes. Poorly recycled end-of-life panels.

We’re told it’s "clean energy," but only if we ignore the dirty front and back ends.

It’s also worth asking: are we solving a food problem—or creating a new tech market for machines, parts, and maintenance contracts?

Nutrients Aren’t the Whole Story

Hydroponic farms can feed plants the exact mix of nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorus they need to grow. They can control pH, lighting, and humidity to create perfect appearances. The lettuce looks fresh. The microgreens taste peppery. The numbers check out.

But there’s mounting evidence that soil-grown food is different in ways we don’t yet fully understand:

- Soil imparts microbial diversity, which benefits gut health and plant resilience.

- Plants grown in soil often contain higher levels of secondary metabolites (like antioxidants), critical for long-term health.

- Nutrients grown in soil may be more bioavailable to our bodies.

In other words, not all lettuce is created equal, even if the label says it has the same vitamins.

What Are We Really Saving?

Let’s talk about people.

Hydroponic farms aim to reduce labour. Automated seeders. Robotic harvesters. AI-powered growth monitoring. The entire business model is often built on the idea that fewer humans equals more profit.

But fewer humans also means:

- Fewer jobs

- Less community involvement

- More isolation

- Less resilience in a crisis

If a machine breaks down, the system halts. If the grid fails, crops die. There is no neighbour to call, no group of hands to step in. We’ve removed people—and with them, adaptability.

Meanwhile, on our microgreens operation, we sow by hand, harvest by hand, package by hand, and deliver by hand. As we scale, even into a future container setup, we aim to keep it this way. Because the value isn’t just in the product—it’s in the process.

The Depression of Disconnection

The push toward hyper-efficiency is not just an economic model—it’s a cultural value shift. It quietly says:

"Let machines handle the work so people can be free."

But free to do what?

Many of us feel our best when we’re useful. There’s dignity in purpose—and farming is one of the most purpose-driven vocations of all. To grow food that nourishes others is deeply fulfilling. It offers connection to the land, to people, and to seasons. When you take that away—when you replace those jobs with automation—you’re not just eliminating labour. You’re stripping away something human.

So what happens when machines take over the productive roles we once did with our hands, our minds, and our communities?

We tell people to go and "enjoy life," as though purpose can be replaced by leisure. But that’s not how we’re wired. Humans crave meaning, not just comfort. We want to build, to serve, to participate.

And for many, that purpose is deeply rooted in contributing to others. The satisfaction of preparing a meal, fixing a tool, growing a tomato—these are not just chores. They are affirmations of belonging and usefulness.

When we remove people from food systems, we do more than eliminate jobs. We erode community structure. In rural towns especially, farms provide rhythm to the year, shared work, neighbourly interdependence. The act of growing and sharing food is one of the most ancient and human expressions of care.

Without it, we isolate people. We send them home with government support and no real place in the local economy. Depression, addiction, and hopelessness rise—not because people are lazy, but because they’ve been removed from the systems that used to need them.

When jobs are replaced with machines, there’s no built-in social structure to catch the fallout. There are no more apprenticeships. No place for an older neighbour to teach. No field to gather in. No shared task to soften hard days.

And while these losses might not show up on a profit-and-loss statement, they show up in our communities: in loneliness, purposelessness, and a widening disconnect from the land, our food, and one another.

Replacing farm jobs with machines might raise profits. But it shatters meaning.

A truly regenerative system doesn’t just restore soil—it restores people.

A Better Comparison: Market Gardens

When people defend hydroponics, they often compare it to industrial monocultures—thousands of acres of the same crop, sprayed with chemicals, harvested by machines. It’s a low bar to clear.

But what if the real alternative isn’t monoculture at all? What if it’s something better?

Compare instead to a soil-based, regenerative market garden:

- It uses compost, compost teas, and cover crops to restore and continually improve soil health.

- It retains water naturally through mulch, living roots, and high organic matter—reducing the need for irrigation and completely eliminating plastic-lined beds.

- It creates local jobs for people of all ages, skill levels, and backgrounds—from youth learning to weed and water, to elders passing down growing wisdom.

- It grows a diverse range of foods, including herbs, flowers, fruit, and vegetables, all adapted to the seasons and the local palate.

- It feeds real people, not just supply chains—CSAs, neighbours, markets, schools, and food banks.

- It encourages resilience by creating networks of growers, not single points of failure.

And just as importantly: it builds community. Market gardens aren’t sterile production units. They are vibrant, biodiverse, living classrooms. Places where people connect to their food, their land, and each other.

Yes, it’s slower. Yes, it’s less "efficient" by industrial metrics. But it’s also more resilient, rooted, regenerative, and rich in meaning.

Because when you ask someone about their favourite food memory, it rarely comes from a factory. It comes from a garden. A farm stand. A grandmother’s hands. That’s the food system worth protecting.

And it’s not just about memory—it’s about motivation. When food is grown not for KPIs, output metrics, or maximum profit margins, but for community growth and shared nourishment, something shifts. We stop chasing volume, and start building resilience.

Imagine if each village, town, or neighbourhood took on the responsibility of feeding itself first. Imagine seasonal eating becoming the norm again. Imagine food prices adjusting naturally—not through subsidies, but through shared skills, local production, and reduced transport. Imagine living within our means—not as sacrifice, but as sanity.

When we grow food with our hands, close to home, with an eye toward our neighbours instead of shareholders, we not only nourish bodies—we restore the balance between people, land, and life.

What Are We Optimising For?

This is the real question:

Are we optimising for profits per square metre—or for people per square meal?

Are we trying to remove the messiness of life from our food—or to reweave food back into the fabric of life?

Because when we optimise solely for output, we lose the richness of input—human input. Real food is messy. It grows crooked sometimes. It needs hands and seasons and patience. It doesn’t arrive in perfect trays wrapped in plastic under LED light.

Food grown for KPIs becomes food divorced from its place, its people, and its purpose.

But when we optimise for local wellbeing instead of distant shareholders, we create systems that are:

- More transparent

- More nourishing

- More responsive to change

- More inclusive to the skills of real people

We create value beyond yield—purpose, connection, and interdependence.

A field isn’t just soil. It’s a place where meaning takes root. A person who plants, tends, and harvests food is not just a worker—they are a steward of life.

A farm without people is not a vision of the future. It’s a symptom of a culture trying to escape itself.

But a field with neighbours, with laughter, with dirty hands and full baskets—that’s a system worth fighting for.

Because what we’re really optimising for isn’t just food.

It’s belonging.

At Oak & Acre, we believe food should grow in soil, in sunlight, and in community. That it should be harvested with care, shared with purpose, and grown in places where people matter as much as the yield.

We're not against technology—we're just for the kind of food system that doesn’t require people to disappear in order to work.

Because food doesn’t just feed bodies. It feeds cultures. It feeds purpose.

And in the end, a truly sustainable future will be grown by hand, not downloaded.